Most of the Episodes on The All Things Wetland Plantst Website have important content associated with each video. However, the YouTube Channel is provided as an alernative way to watch the Video Series, with no added content.

Click here to view the Video Series from the ATWP YouTube Channel.

If you would like to receive an email notice when we release a video, please subscribe to the ATWP YouTube Channel by clicking on the Subscribe button.

Video Series OverviewThis video series is designed to provide information on wetland plants with a focus on wetland plant identification in an unscripted, relaxed format. Videos will consist of lectures, discussions, and interviews with local experts from across the country.

Discussion materials, such as slides, diagrams, lists of common plant species, and regional field guides to common wetland plants will be available for download. We will also provide links to helpful websites and electronic keys. The National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) website, how to get information on wetland ratings, and how to submit comments will also be discussed.

To provide regionally relevant information on plants across the nation, we will interview herbaria curators, researchers, and expert local botanists. We will also provide overviews of wetland plant studies pertaining to delineation, restoration, and mitigation.

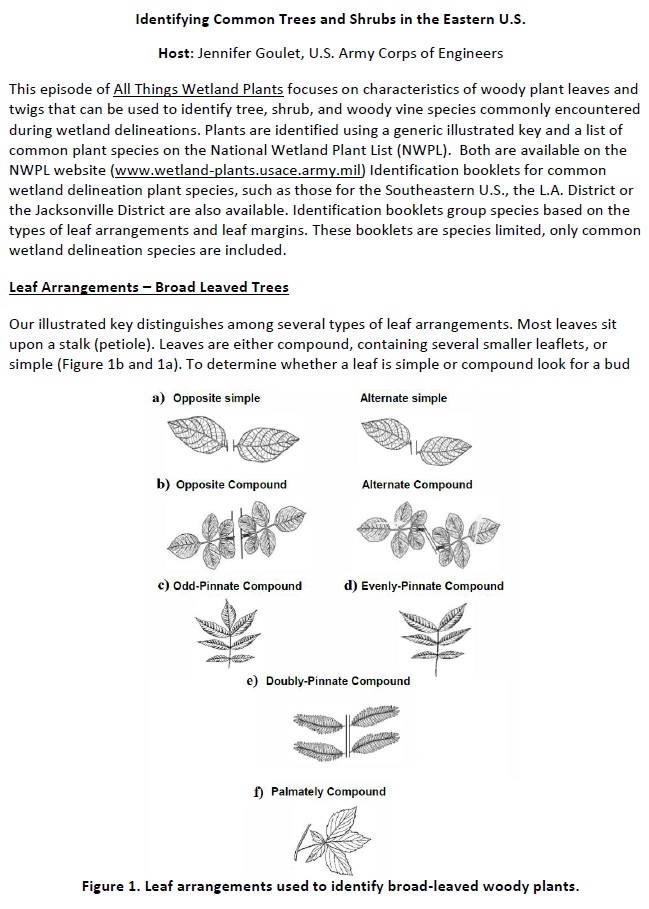

Episode 1a: Overview of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series"Common" is the theme for the plant identification component, with a focus on wetland boundary species. Many of the same species occur in wetlands across the country. Common species make up a small percentage of regional floras. We will show you how to use field guides we developed to identify common wetland plant species. Links to list of the most common wetland plant families, genera, and species, nationally, regionally, by Corps District, and by state are at bottom of this webpage. This class will examine basic plant morphology in the field with a 10x hand lens, concentrating on the critical features needed to identify vascular plant species. Diagrams of and pictures of these basic morphological features and the regional field guides will be available as downloads to make it easy to follow along.

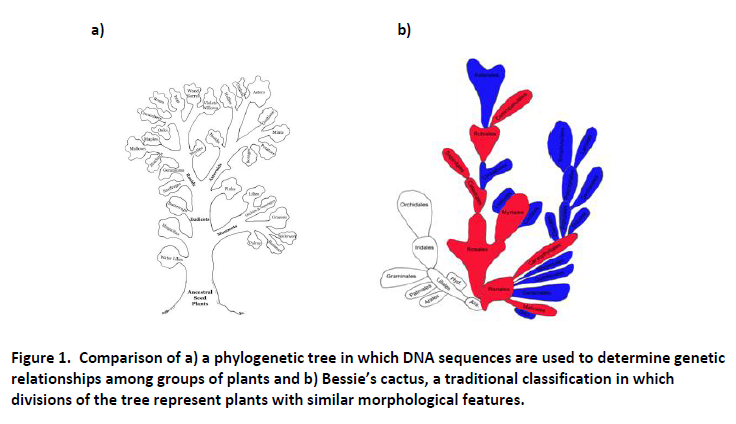

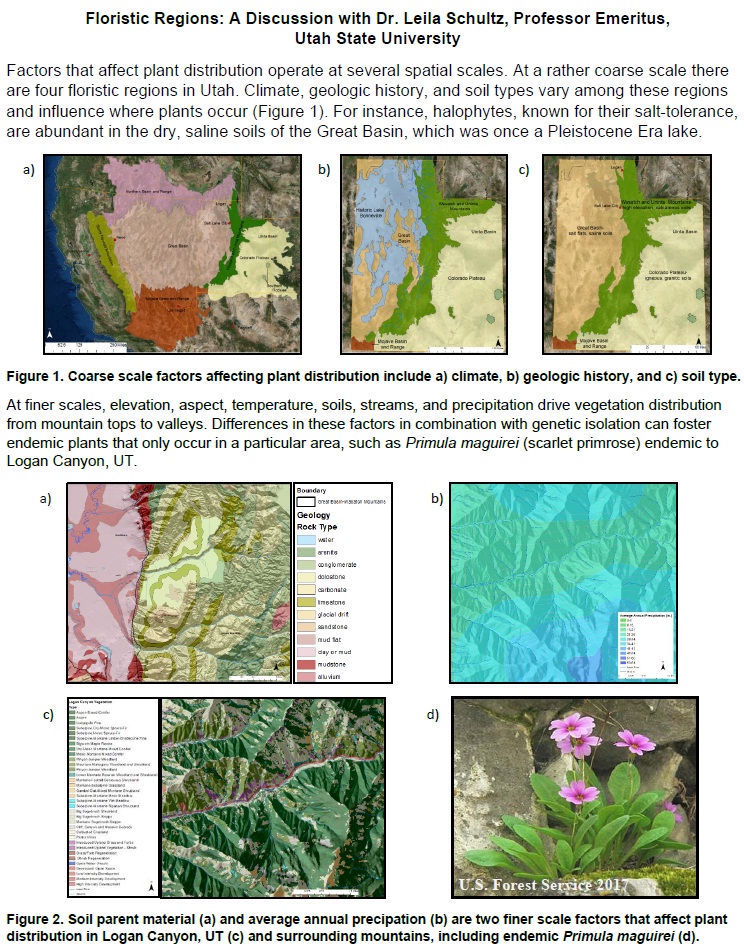

Taxonomy and NomenclatureOur first topic is how taxonomy and nomenclature affect wetland plant names and ratings. Taxonomy is the name of a plant. Nomenclature refers to tracking names as they change over time, according to rules developed by the International Botanical Code. Different approaches to plant classification can cause names to change over time (Figure 1). Traditionally, plants were classified based on morphological features (Figure 1b). Carl Linnaeus, famous for developing a binomial system for naming plants, also developed a sexual system for classifying plants. Traditional classification systems, such as Bessie's cactus, presumed plants with similar features, such as a particular type of ovary, were closely related, evolutionarily. The more recent phylogenetic species concepts are based on DNA sequencing and analysis (Figure 1 a).

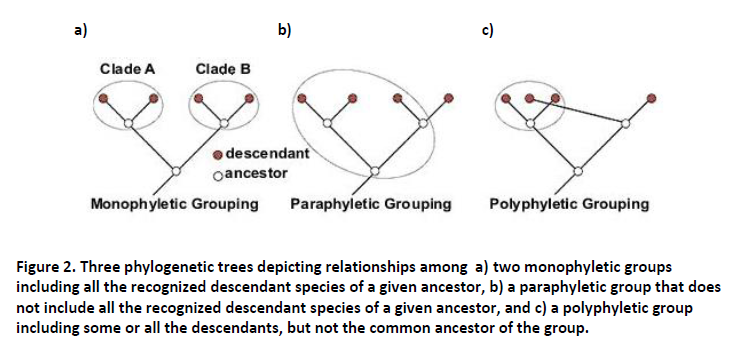

The phylogenetic trees built from these analyses are used to show genetic relationships among species. Species and genera should be monophyletic groups, meaning that they originate from a common ancestor. However, sometimes, phylogenetic analyses reveal that several species traditionally thought to be closely related are actually a polyphyletic group, originating from different ancestors (Figure 2 c). In this case, one species is renamed. Its old name becomes a synonym. The National Wetland Plant List website accepts both synonyms and current, accepted names in the search box. If a synonym is entered, the website automatically redirects you to the currently accepted name so that you can get the wetland rating. This class will provide handouts listing and explaining some of the recent changes to wetland genera, such as Scirpus L. or Aster L.

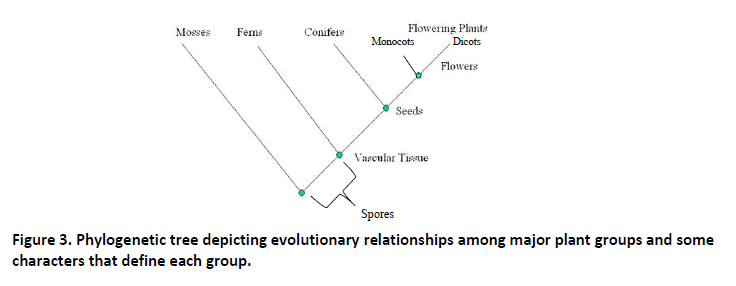

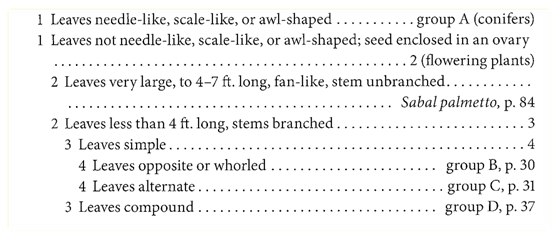

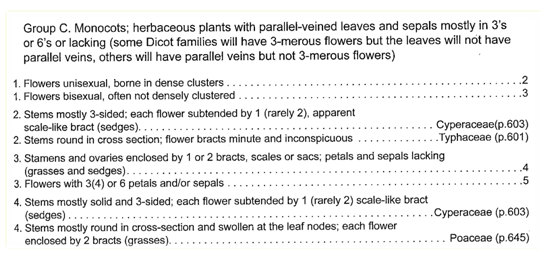

Regional floras are applied technical manuals that help you identify plants. They used to be arranged according to traditional morphological species concepts. Most modern floras are arranged alphabetically and do not imply genetic relationships among taxa. Most regional floras contain several thousand species, most of which are not common. We will use field guides of regionally common species to identify common wetland plants. These botanical keys are designed to take you quickly a major plant group. Major groups of vascular plants include ferns, conifers, and the flowering plants, a group composed of monocots and dicots (Figure 3).

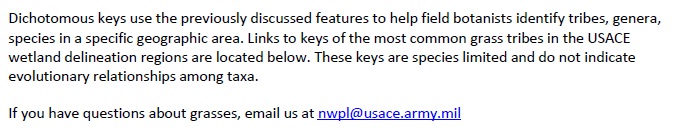

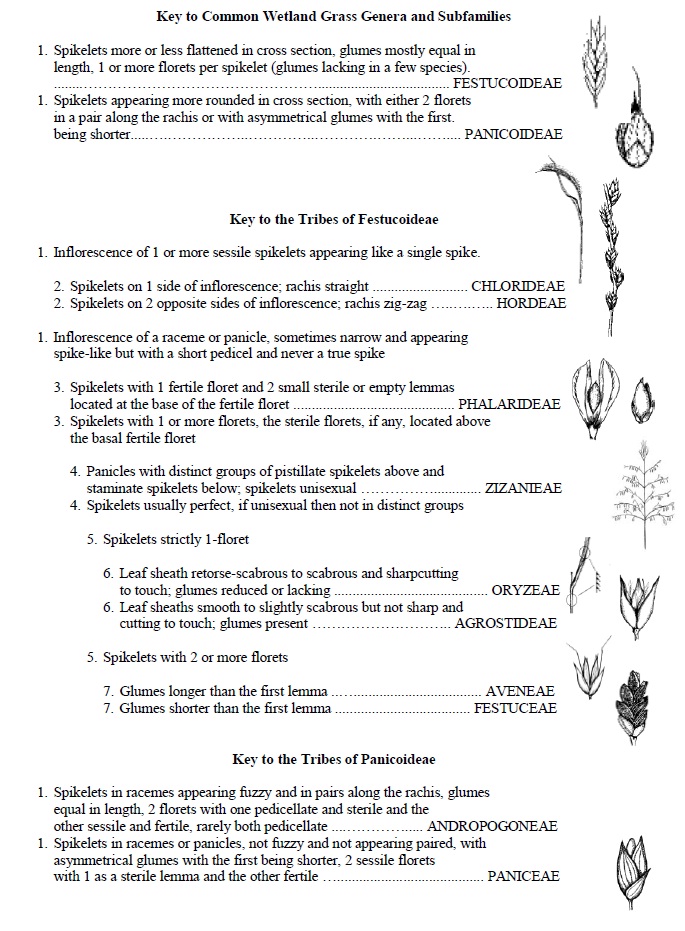

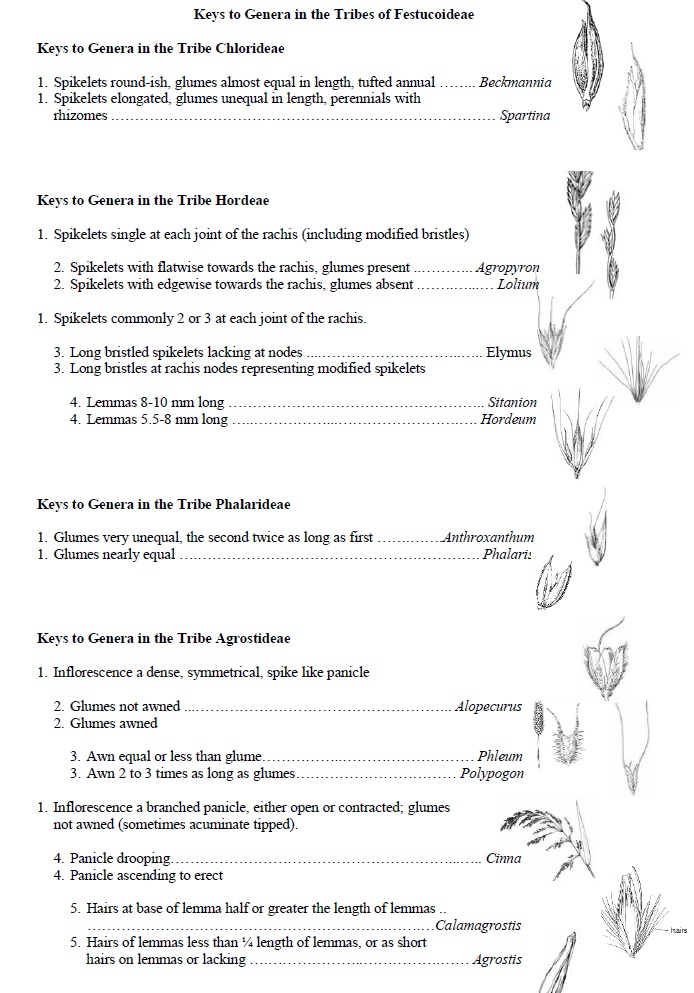

We will work at the taxonomic levels of families, tribes genera, and species. Tribes are used primarily in large families, such as the asters or the grasses. Tribes are groups of genera and species with similar morphological features that are easy to see in the field. These groups make the species easier to identify and quicker to learn. We will start with identification of common flowering plants in the summer and move on to common woody shrubs and trees in the winter. Not much time will be spent on aquatic plants, or "floaters", because wetland delineations focus on plants at the boundary. Our goal is for you to have a packet of regionally relevant plant lists and field guides to common plants based on botanical terms, concepts, and approaches, to take into the field and help you identify plants.

Episode 1b: Introduction to Plant IdentificationThe Natural History of Ferns with Paul Wolf, Professor, Utah State University

Episode 2a of All Things Wetland Plants is the first part of an interview with Paul Wolf, Professor, Utah State University. He discusses the natural history of ferns, including evolution, distribution, phylogeny, and lifecycle.The second part, Episode 2b, will focus on key features used to identify ferns.

What is a Fern?

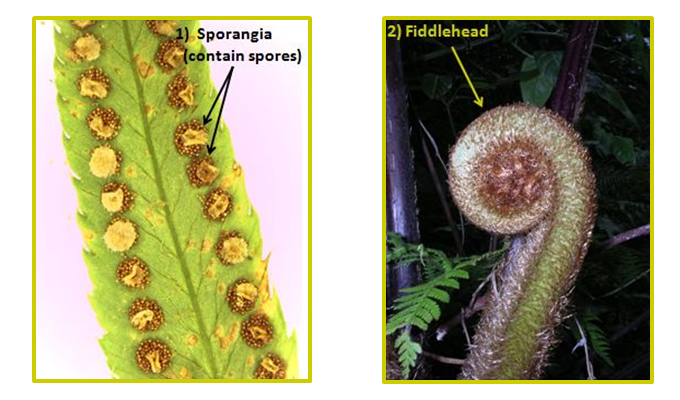

There is no single characteristic that is unique to ferns, except that they all share a common ancestor about 350 million years old. Ferns reproduce by spores and have true leaves that originate from a coiled fiddlehead (Figure 1). Fiddleheads of certain species, such as ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), are edible. Others, such as the bracken ferns (Pteridium spp.), are toxic when eaten in large quantities.

Figure 1. Features common to most ferns include 1) reproducing by spores, and 2) true leaves that emerge from coiled fiddleheads.

Many ferns also have rhizomes, underground stems that produce roots and fronds. In terrestrial ferns, rhizome structure influences growth form, making plants appear either clumped or scattered (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Some fern growth forms: 1) clumped, Polystichum munitum; 2) creeping or scattered, Diplazium subsinuatum; 3) epiphytic, Lygodium japonicum; and 4) aquatic, Salvinia molesta.

Another growth form is that of epiphytic ferns, which grow on top of other plants. Adaptations such as leaf scales help them absorb water and nutrients. Epiphytic ferns are most common in tropical rainforests and cloud forests, but some occur in the U.S. (i.e. Polypodium spp.). Aquatic ferns, which float or root in standing water, represent a fourth growth form. Many of these do not look like ferns, but when examined closely, true leaves that develop from a coiled fiddlehead are visible. Ferns also contain pigments that enable them to photosynthesize under the low light conditions common in forest understories, both temperate and tropical. Most ferns are fairly long lived perennials. Tropical tree ferns can live 30-40 years. However, some aquatic species have shorter life spans.

Evolution

Ferns first occur in the fossil record in the Carboniferous Period (300 - 250 million ybp). But, most ferns (80%) trace their origins to the Cretaceous Period (100 - 200 million ybp) that ended with a mass extinction event. This event may have been caused by an asteroid-earth collision that filled the atmosphere with dust and ash, blocking sunlight for months or years. The fossil record suggests that the ferns that survived quickly colonized the earth and were quite abundant when compared to the flowering plants that survived. Today there are an estimated 12,000 - 15,000 fern species worldwide, but only 9,000 have been described and named.

Distribution

Ferns are most diverse in the Tropics and southeast Asia. In the U.S., the east probably has a larger number of fern species, but the west has greater fern abundance and biomass. Ferns grow in many different habitats, including deserts, alpine areas, rainforests, cloud forests, and in aquatic settings. Habitat preference is species specific, but the majority of ferns occur in uplands. Most ferns prefer mesic habitats with well-drained, oxygenated soils. However, there are a few wetland species that tolerate boggy, waterlogged soils. However, a group of related plants, the horsetails (Equisetum spp.), are more likely to occur in wetlands.

DNA-Phylogeny

Genetic analyses have resolved many questions regarding evolutionary relationships among fern taxa. Although this work has revealed many strong character traits that define small subgroups, field identification can still be difficult. For instance, the largest fern family, the Dryopteridaceae (Wood Fern Family), has no single character that defines it. Dichotomous keys eliminate all the other fern families, before arriving at this family. The same is true of the genus Dryopteris.

In ferns, chloroplast genes were first used for DNA sequencing. Now, scientists are sequencing the entire genome. Like flowering plants, ferns frequently double their chromosome counts (ploidy levels) when reproducing. One Himalayan species has more than 1,400 chromosomes. In ferns, as the number of chromosomes increases, genome size also increases. This is not true of all plants, however. A typical fern genome may be three to five (to ten) times as large as a human genome.

Fern Lifecycle

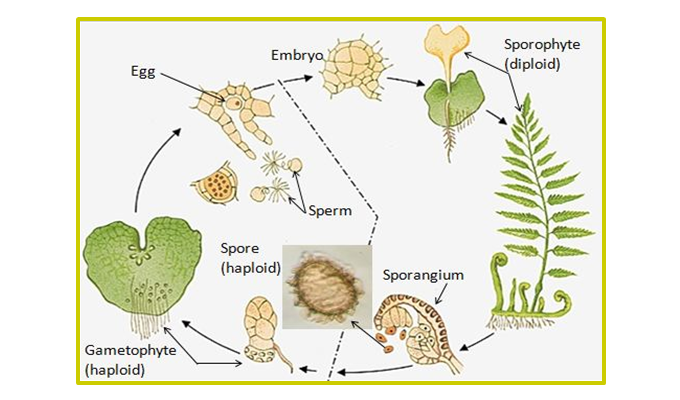

Ferns reproduce by spores which are haploid (half the chromosomes of the parent plant), as are animal gametes, egg and sperm. Unlike animal gametes, fern spores do not immediately combine to produce a new diploid individual (Figure 3). Spores have ridges and flaps to catch the wind for dispersal. When a spore lands in a suitable habitat; it grows into a haploid gametophyte, severalmm long. The gametophyte produces gametes (eggs, sperm). Sperm swim though soil moisture to fertilize an egg. They unite to form a diploid embryo that grows into a fern.

Figure 3. Fern life cycle alternates between the diploid sporophyte and the haploid gametophyte, an independent sexual stage that produces gametes (sperm, egg).

Episode 2a: Natural History of Ferns : with Paul Wolf Watch on Youtube Download Documents - Natural History of Ferns Natural History of Ferns Document (docx) Figures for Natural History of Ferns (pdf)Identifying Ferns with Paul Wolf, Professor, Utah State University

Episode 2b of All Things Wetland Plants is the second part of an interview with Paul Wolf. In the last episode (2a), he discussed the natural history of ferns, including evolution, distribution, phylogeny, and lifecycle. This video focuses on five groups of morphological features used to identify ferns.

Growth Form

Fern growth form refers to leaf structure and arrangement (Figure 1). The growth form of some terrestrial ferns is clumped, consisting of many fronds that emanate from a single rhizome and form a rosette-like pattern. Others have a creeping or scattered form, with each frond connected to a long linear or branching rhizome. Epiphytic ferns grow on top of other plants. Aquatic ferns are either free floating or have roots that anchor them in standing water. Many do not look like ferns, but close examination reveals true leaves that develop from a coiled fiddlehead.

Figure 1. Some fern growth forms: 1) clumped, Polystichum munitum; 2) creeping or scattered, Diplazium subsinuatum; 3) epiphytic, Lygodium japonicum; and 4) aquatic, Salvinia molesta.

Vascular Tissue

Xylem and phloem, which conduct water and carbohydrates, are grouped in bundles running through the stem and into the leaf. Vascular bundles have a stringy appearance when peeled, like those in celery. The number and shape (e.g. smiley face) of these bundles in a stem cross-section (Figure 2) is an important characteristic for distinguishing among groups of fern families or genera. These features are best seen in a cross-section cut from the base of the frond.

Figure 2. Vascular bundle arrangement and paper scales at the base of a Polystichum spp. frond.

Leaf Shape

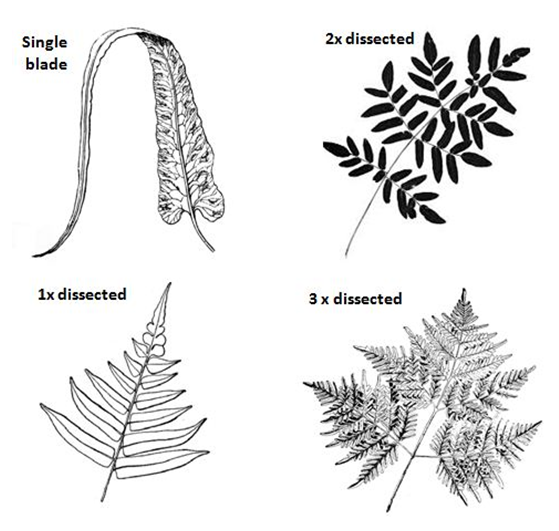

In ferns, leaf shape is categorized based on dissection, the number of times the frond divides (Figure 3). Fronds may be entire or divided into pinnae. Dissection may be a good indicator of a group of genera. Sometimes dissection is a strong characteristic of a particular genus, but not always. This characteristic is most useful in small scale, local keys.

Figure 3. Examples of leaf division in ferns.

Hairs and Scales

The shape and color of hairs (Figure 4.1), papery scales (Figures 2 and 4.2), may be useful for identifying some groups of ferns. In the bracken ferns (Pteridium spp.), the type of hair and its shape are diagnostic. These features may be located on stems or leaves. Likewise, spines on the leaf margins (Figure 6.1) are characteristic of some genera, such as Polystichum spp.

Figure 4. Examples: 1) hairs on the under-side of a Pteridium spp. frond,

and 2) papery scales on a coiled Cyathea spp. fiddlehead.

Reproductive Structure

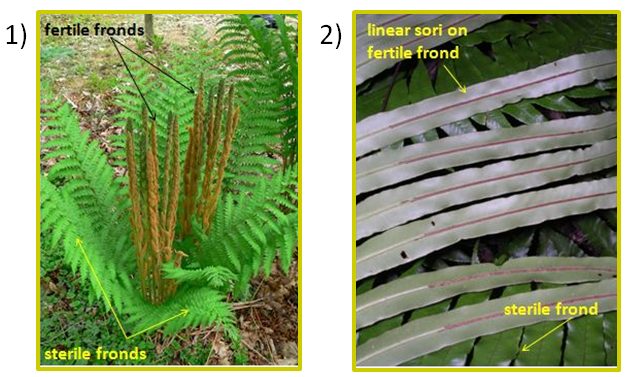

Monomorphic ferns have one type of leaf, with reproductive structures on the back. In dimorphic ferns the reproductive structures are located on specialized, fertile leaves. The remaining leaves are sterile. The fertile and sterile fronds may be very different in appearance or they may be fairly similar (Figure 5).

Figure 5. On sterile and fertile fronds on dimorphic ferns may be quite different in appearance,

as in 1) cinnamon fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum), or

2) fairly similar as in centipede fern (Blechnum orientale).

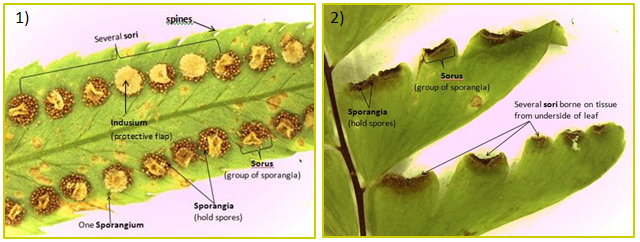

Reproductive structures include spores, sporangia, sori, and indusia. Spores are produced in sporangia, which are usually grouped in clumps, called sori. The shape and location of sori and sporangia are diagnostic. For example, sori may occur throughout the underside of the leaf. They may also be round and arranged in clusters (Figure 6.1). Others are kidney-shaped. Linear sori may arranged in one (Figure 5.2) or several rows. The number of rows is an important feature.

Sporangia may be marginal, located on leaf edges (Figure 4.1), or borne on the underside of the leaf that curls over the margin (Figure 6.2). In some genera, sori are covered by an indusium, a flap of protective tissue that shrivels up as it dries (Figure 6.1). A large fern, such as sword fern, produces millions of spores that are wind dispersed. Endemism rates are low in ferns when compared to flowering plants because the jet stream disperses fern spores between continents, creating unusual hybrids and worldwide distributions for most genera.

Figure 6. Figure 6. Examples of sporangia, sori, and indusia,

in 1) sword fern (Polystichum munitum)

and 2) maiden-hair fern (Adiantum spp).

Identifying Ferns for Delineation Purposes

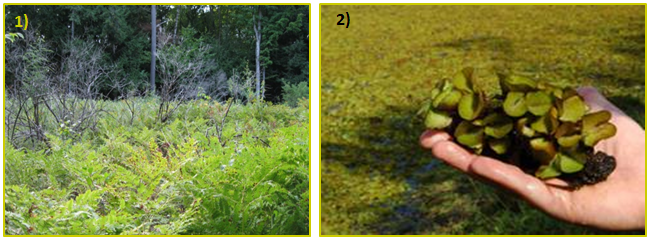

Some fern species are habitat specialists restricted to specific environmental conditions, such as moist conditions near waterfalls or hot, dry deserts. Others are habitat generalists found in a wide range of habitats. For example, a long, creeping, growth form enables an individual bracken fern (Pteridium spp.) to grow in shade and full sun. This species also thrives in disturbed situations, such as clear-cuts (Figure 7). Likewise, Salvinia spp. is an aquatic fern that is considered a noxious weed in southeastern U.S., invading aquatic systems and clogging dams.

Figure 7. 1) On this hillside powerline where woody plants are regularly cut and treated with

herbicide: bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), hay scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula),

interrupted fern (Osmunda claytonia), and sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) are common,

2) Salivina molesta invades aquatic systems, choking out native plants.

Dichotomous keys use the previously discussed features to help field botanists identify ferns in a specific geographic area. Keys to large geographic areas begin with a key to families that uses features representative of evolutionary relationships (i.e. number and shape of vascular bundles) to distinguish among the fern families. Keys to genera and species use features that may or may not indicate evolutionary relationships among taxa. These include growth form, leaf shape, hairs, scales, and reproductive structures, such as sori, indusia, and dimorphic fronds. Use a local flora for delineation purposes because the features that distinguish among the ferns in your locality are different from the features used to distinguish among the 12,000 - 15,000 species of ferns worldwide.

Episode 2b: Watch on Youtube Download Documents - Identifying Ferns Key Features for Fern Identification (docx) Figures used in Fern Identification (pdf) NWPL Field Identification Guides Field Guide Printing Instructions (pdf)Episode 3 of All Things Wetland Plants explains the recently posted lists of the ten most common wetland plant families in the nation, the Corps wetland regions, the states, and the Corps Regulatory Districts. As this series progresses, dichotomous keys to the species on these lists will be posted for each region.

What is Common?

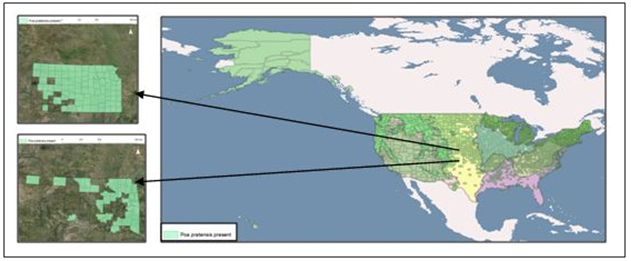

The National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) database contains a record of each species presence or absence, for each county in the United States. Families, genera, and species present in more than half of the counties in a geographic area were considered common. Commonness varied with spatial scale (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A common species Poa pratensis (Kentucky Blue Grass), is present in more than half the counties in the United States. It is present in less than half the counties in the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain region and Oklahoma.

Kentucky Blue Grass (Poa pratensis) is common nationally, but not in all regions. It was not common in the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. At the state level, Kentucky Blue Grass may be common or not, as in Kansas and adjacent Oklahoma, respectively. In small states with very few counties, such as Delaware, only the species present in all counties were considered common.

Species from large families, such as the grasses, asters, and sedges, were more likely than those from smaller families to be considered common. Yet, species from small families with very few species on the NWPL, such as Boxelder (Acer negundo), may still occur in more than half the counties in the nation (Figure 2). Regional keys to special plant groups, such as woody plants or ferns, will address this type of common species.

Figure 2. Boxelder (Acer negundo) is common, occurring in more than half the counties in the nation. It is not on the lists because it comes from a small family with few species on the National Wetland Plant List.

Episode 3: What is Common? Watch on Youtube Download Documents - What is Common? Plant Identification - What is Common? (docx) Figures used for What is Common? (pdf)Common Species Tables

Common Species Tables, for the most common plant taxa on the National Wetland Plant List 2014, have been created for various geographies including: Nationally, USACE Wetland Regions, USACE Districts and US States. The ten most common families are included in the Common Species Table for each geography. Listed under each common family are the most common genera and species. In most cases these occur in more than half the counties of each specific geography. Please see the links below to download Common Species tables.

Download National and USACE Wetland Regions Common Species Tables

Contains Tabs for Common Species Nationally and for each USACE Wetland Region.

National and USACE Wetland Regions Common Species Tables

Download Common Species Tables for USACE Districts by Division

Each XLS file contains a Tab for each District in a Division.

| LRD | Districts of the Lakes River Division |

| MVD | Districts of the Mississippi Valley Division |

| NAD | Districts of the North Atlantic Division |

| NWD | Districts of the Northwestern Division |

| POD | Districts of the Pacific Ocean Division |

| SAD | Districts of the South Atlantic Division |

| SPD | Districts of the South Pacific Division |

| SWD | Districts of the Southwestern Division |

Download Common Species Tables for U.S. States

|

|

|

|

|

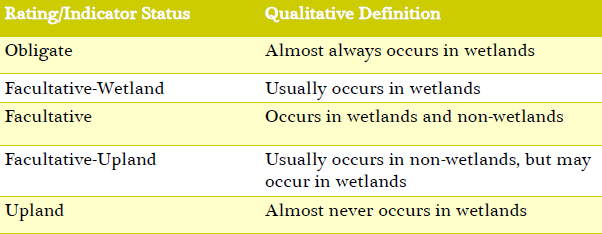

Wetland Ratings

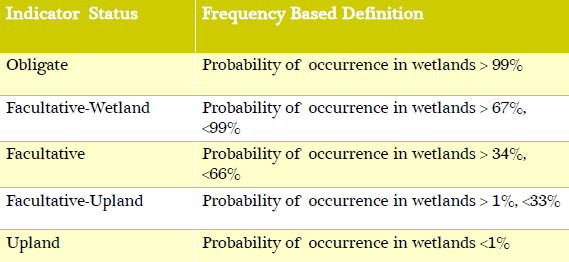

Episode 4 of All Things Wetland Plants discusses the history and definitions of indicator status ratings on the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL). A national list of plant species that occur in wetlands was developed in 1988 to support federal agencies in field identification of wetlands. In 2006, the US Army Corp of Engineers assumed responsibility over the list and it became known as the National Wetlands Plant List. Since then, the list has been updated with current plant name changes and indicator status ratings. Overall the list is meant to clarify the meaning of hydrophytic vegetation under the clean water act, the Wetland Conservation Provisions of the Food Security Act, and to serve in wetland restoration and creation projects. Each plant species on the NWPL has an indicator status which reflects the likelihood of presence in a wetland. The following are the accepted qualitative definitions of the five indicator status categories:

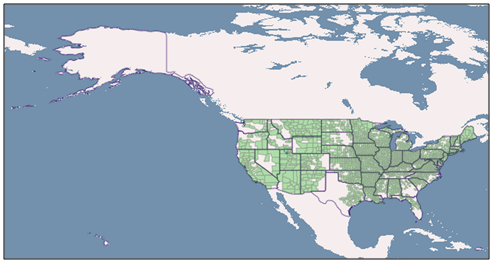

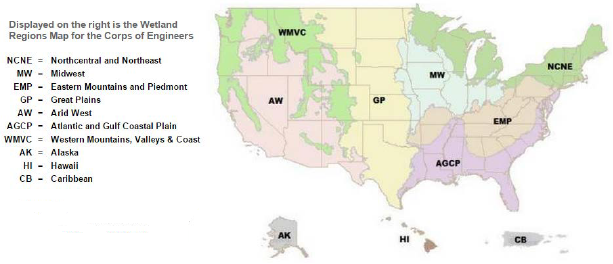

Species were placed in these categories based on a national and regional panel review process that included botanists and ecologists from the FWS, Army Corp, EPA, and NRCS. Ratings were assigned to plant species separately within each of the ten Corp Wetland Delineation Regions (Figure 1). To inform these ratings the panels used best professional judgment and available literature, as well as feedback from universities, the private sector, and the public.

Ratings were assigned to plant species separately within each of the ten Corp Wetland Delineation Regions (Figure 1). To inform these ratings the panels used best professional judgment and available literature, as well as feedback from universities, the private sector, and the public.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Those familiar with the plant list may remember quantitative frequency based definitions for the indicator status categories:

We are using the newer, qualitative definitions rather than the quantitative definitions for all species on the NWPL. This is because a frequency definition alone implies that the wetland ratings were based on actual sampling of plant species populations, which is not the case for most plants on the NWPL. We are retaining the quantitative frequency based definition for any future challenge studies regarding the current accepted NWPL rating and for those species where field sampling has occurred and a frequency has been determined.

In the interview portion of this segment, we address in more detail the background of wetland plant ratings, how to look up species and their indicator status rating on the NWPL website, what to do if you disagree with a wetland rating, and additional commonly asked questions about the NWPL.

Some questions and answers from the interview include:

Why can't I find a species on the NWPL? The NWPL is not an exhaustive list of all plant species that may be encountered in a wetland delineation. It only includes species that have been given an indicator status rating. If you are failing to find a plant species on the NWPL website, it may be the result of a spelling error. You may consider typing a portion of the genus name into the search bar and looking for the specific species this way.

How does the NWPL treat subspecies and varieties? What to do if I have only keyed to genus? The lowest taxa level wetland ratings are assigned to on the NWPL is species. Infraspecific taxa are not assigned wetland ratings. Thus, for the purposes of wetland delineation, there is no need to key past species. Indicator statuses are not assigned to genera on the NWPL. Thus, you will need to key to species for an indicator status. Fortunately, there is no effect on hydrophytic vegetation determinations if 80% rather than 100% of the vegetation cover is used for calculations. So if removing your unknown plant specimen from the sample retains at least 80% of the plot cover, you do not need to key it.

Episode 4: Wetland Ratings Watch on Youtube Download Documents - Wetland Ratings Plant Identification - Wetland Ratings (docx) Figures used in Wetland Ratings (pdf)Episode 5 of All Things Wetland Plants discusses various resources for keying out unfamiliar plant species.

Field Guides

Field Guides contain brief descriptions and photographs of the most common species in an area. They are not dichotomous keys.

Illustrated Glossaries

Illustrated Glossaries contain definitions and line drawings of botanical terms.

Dichotomous Keys

Dichotomous keys are composed of couplets. Each couplet consists of two choices. After selecting the choice that best describes your plant, you are directed either to a family, genus, species or to another couplet.

Dichotomous keys cover different geographic areas, including states (Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, by P. Lesica), regions (Native Trees of the Southeast: an Identification Guide, by L. K. Kirkman, C.L. Brown, and D. J. Leopold.), or continents (i.e. Flora of North America (FNA), FNA Committee). Keys that cover larger areas are broader and contain more species than local floras. Keys are structured in one of two ways:

Dr. William Weber is a retired professor of botany and natural history at Colorado University in Boulder, curator emeritus of the Colorado University Museum of Natural History, and a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London. Along with Ron Wittmann, he has published many works in the Colorado Flora Series, most recently Colorado Flora: Eastern Slope (2012) and Colorado Flora: Western Slope (2012). Dr. Weber is also an accomplished bryologist and lichenologist. He authored Bryophytes of Colorado: Mosses, Liverworts and Hornworts with Ron Wittmann (2007) and A Rocky Mountain Lichen Primer with James Corbridge (1998). Dr. Weber developed hypotheses about the origin and distribution of alpine floras based on his world-wide botanical studies. As curator of the Colorado University Museum of Natural History Herbarium collection, Dr. Weber developed plant collections which today consist of more than half a million specimens. The collection was named the W.A. Weber Collection in 2012.

A Discussion of HerbariawithDr. William Weber retired botany professor and curator emeritus of the Colorado University Museum of Natural History

In this interview, Dr. Bill Weber discusses standards for herbaria organization, collecting methods, what to do with unknown plant species, and why recording accurate locations of plant species is important for understanding the distribution of plant species. He stresses the importance of specimen preservation and shares a brief history of herbaria, which includes the loss of monocot collections from the Vienna Museum during World War II. Dr. Weber also describes his background and the opportunities that took him across the U.S. collecting and identifying plants and eventually developing a nationally recognized herbarium at the University of Colorado in Boulder (CU Boulder) from acquired private botanical collections.

Episode 6a: A Discussion of Herbaria : with Dr. William Weber Watch on Youtube Download Documents - Dr. William Weber A Discussion of Herbaria (docx)A Lifetime of BotanywithDr. William Weber retired botany professor and curator emeritus of the Colorado University Museum of Natural History

In this interview, Dr. Bill Weber discusses standards for herbaria organization, collecting methods, what to do with unknown plant species, and why recording accurate locations of plant species is important for understanding the distribution of plant species. He stresses the importance of specimen preservation and shares a brief history of herbaria, which includes the loss of monocot collections from the Vienna Museum during World War II. Dr. Weber also describes his background and the opportunities that took him across the U.S. collecting and identifying plants and eventually developing a nationally recognized herbarium at the University of Colorado in Boulder (CU Boulder) from acquired private botanical collections.

Episode 6b: A Lifetime of Botany : with Dr. William Weber Watch on YoutubeA Reading on the Concept of a GenuswithDr. William Weber retired botany professor and curator emeritus of the Colorado University Museum of Natural History

In this episode, Dr. William Weber reads a letter addressed to him by the late botanist Dr. Theodore "Ted" Barkley, excerpted from Dr. Weber's Colorado Flora. In this letter, Ted commends the use of genera to represent clades or evolutionary relationships, as Dr. Weber has spearheaded, rather than a potentially unjustified collection of species. This has resulted in much splitting of traditionally accepted genera in Weber's floras, but has led to a better understanding of the evolutionary history and relationships among different plants, with important implications for conservation and land management.

Episode 6c: A Reading on the Concept of a Genus : with Dr. William Weber Watch on Youtube Download Documents - Dr. William Weber Concept of a Genus Reading (docx)Episode 10 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Brief Review of Major Features to Key Common Wetland Ferns

With Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps Of Engineers

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program.

Episode 9 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

This episode provides an overview of the natural history of Savannah lowland swamps.

Host: Robert Lichvar (Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers).

Presented by: David Lekson (Chief, Regulatory Division, Savannah District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

Episode 10 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar (Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers).

Special Guest: Robert Dorn (Willow Specialist, retired)

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 11 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar ( Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ).

Special Guest: Dr. Gary Laursen ( Professor of Biology, Universtity of Alaska Fairbanks )

Cameo Appearance: Dr. Paul Wolf ( Professor, Utah State University )

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 12 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guests: Melinda Peters, Museum Specialist, U.S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution,

Dr. Paul Peterson, Research Botanist and Curator, U.S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution

Extras: Andrew Blackburn, Regulatory Project Manager, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Dr. Gabrielle David, Research Hydrologist, Science and Technology Corporation

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 13 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Paul Peterson, Research Botanist and Curator, U.S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 14 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guests: Dr. David Cooper, Professor, Colorado State University,

Dr. Edward Gage, Post-doctoral Research Scientist, Colorado State University

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 15 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Filming: Lindsey Lefebvre Editing: Matthew Mersel Technical Inserts: Jennifer Goulet

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 15: Identifying Common Wetland Flowering Plant FamiliesEpisode 16 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Leila Shultz ( Professor Emeritus, Utah State University )

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

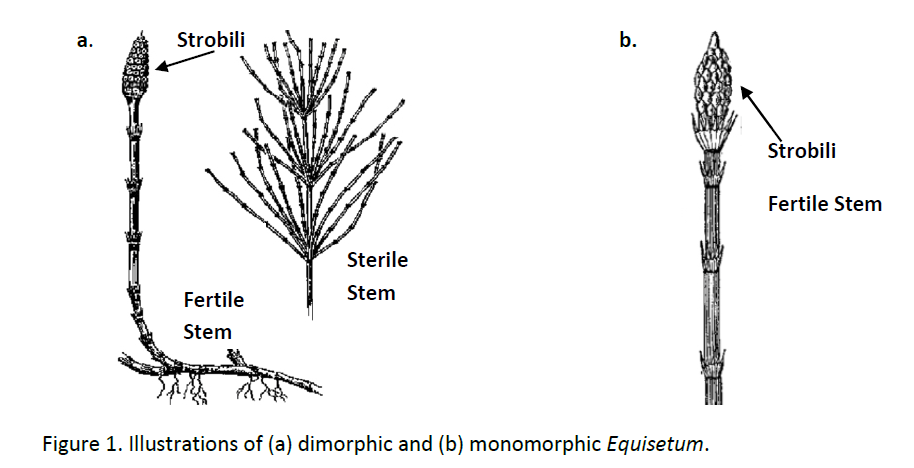

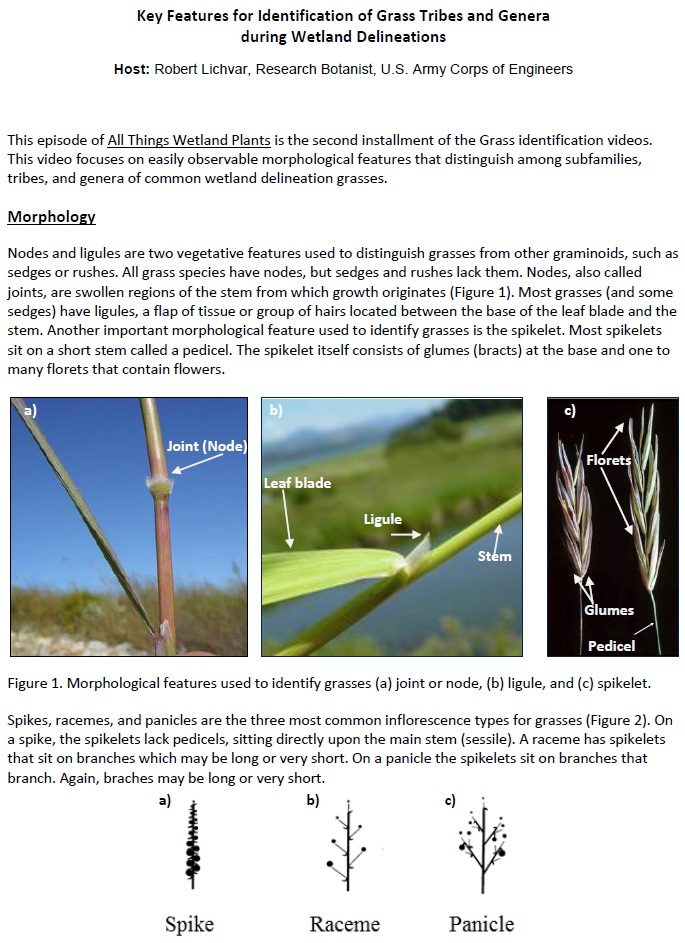

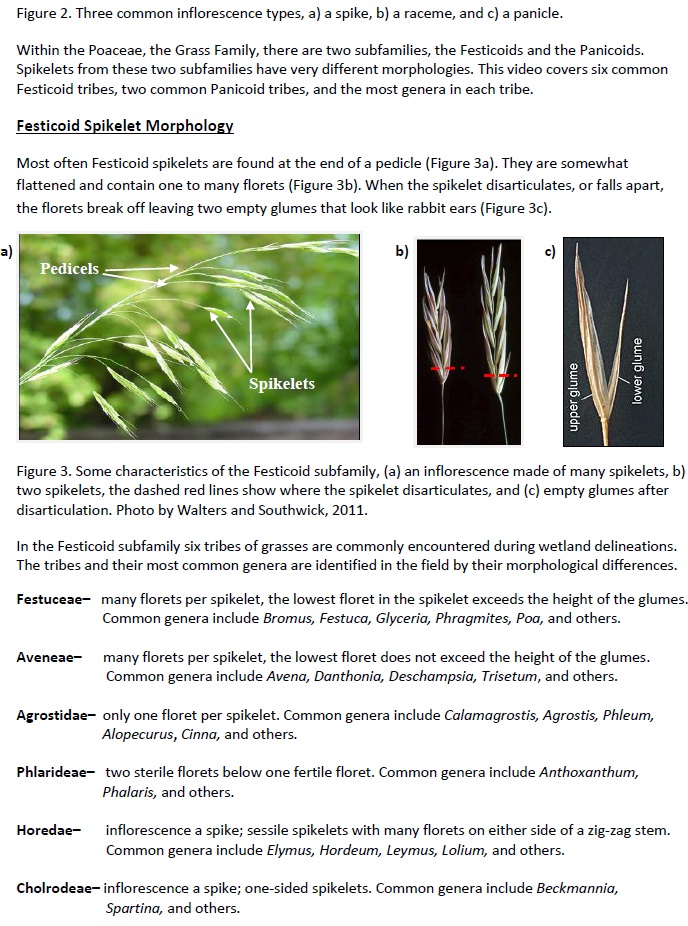

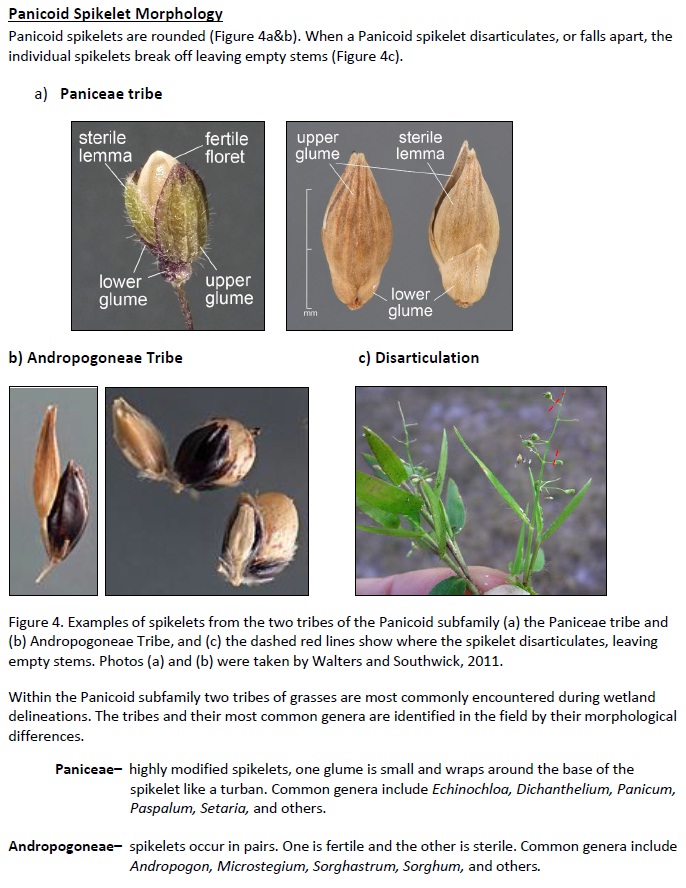

This episode of All Things Wetland Plants focuses on the morphological features used to identify common species of Equisetum, or Horsetails, encountered during wetland delineations. There are three important features, growth forms, branches, and leaf sheaths.

Growth forms:Dimorphic Equisetum have two growth forms (Figure1a). The fertile stalks emerge in the early spring. They are easy to recognize by their lack of green pigment and the reproductive structures, called strobili, at the top of the stem. Sterile stems, which are green and lack strobili, emerge later in the spring after the fertile stems die back.

Monomorphic Equisetum have one growth form (Figure1b). All stems are fertile with green pigmentation and strobili at the top.

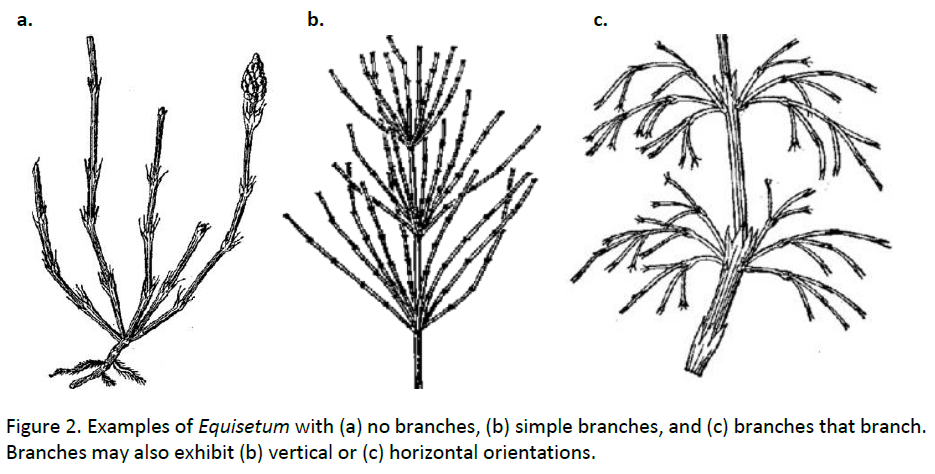

Some species of Equisetum lack lateral branches (Figure 2a). Others have simple lateral branches (Figure 2b). Another species has branches that branch (Figure 2c). Equisetum keys may also ask if the branches have a vertical (Figure 2b) or a horizontal (Figure 2c) orientation.

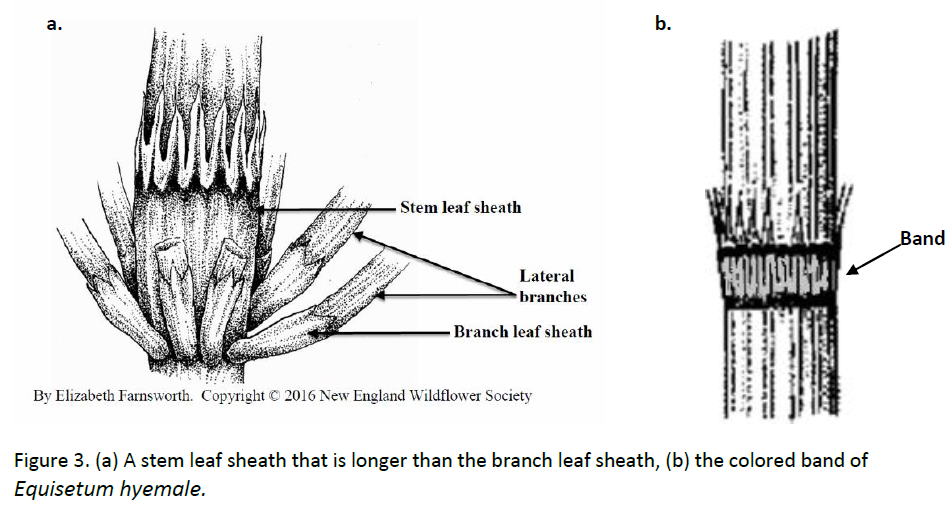

In Equisetum the leaves are reduced to sheaths, or collars, that encircle the stem and lateral branches. When keying Equisetum you may need to determine if the leaf sheath of the lowest branch is longer than the leaf sheath on the stem (Figure 3a). In the unbranched Equisetum, the leaf sheaths have a colored band used to identify the species. Equisetum hyemale, the species in Figure 3b, has a gray band.

Dichotomous keys use the previously discussed features to help field botanists identify Equisetum species in a specific geographic area. Links to keys to the most common Equisetum in the USACE wetland delineation regions are located below. These keys are species limited and do not indicate evolutionary relationships among taxa.

Episode 16: Identifying Common Equisetums Watch on Youtube NWPL Field Identification Guides Field Guide Printing Instructions (pdf)Episode 17 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Special Guest: Dr. Leila Shultz ( Professor Emeritus, Utah State University )

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

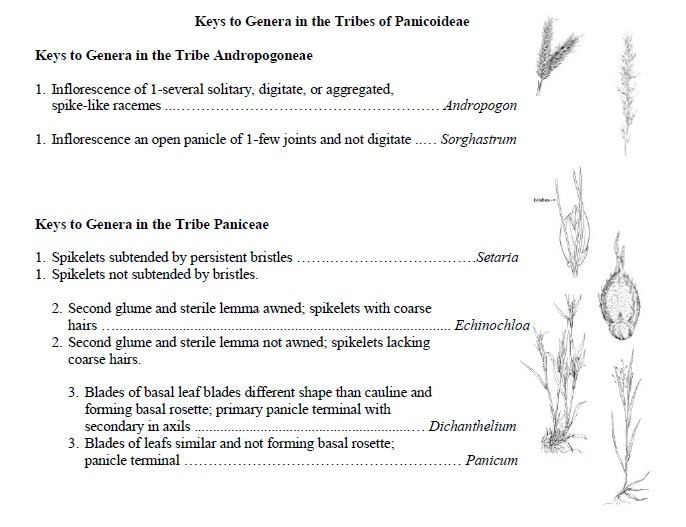

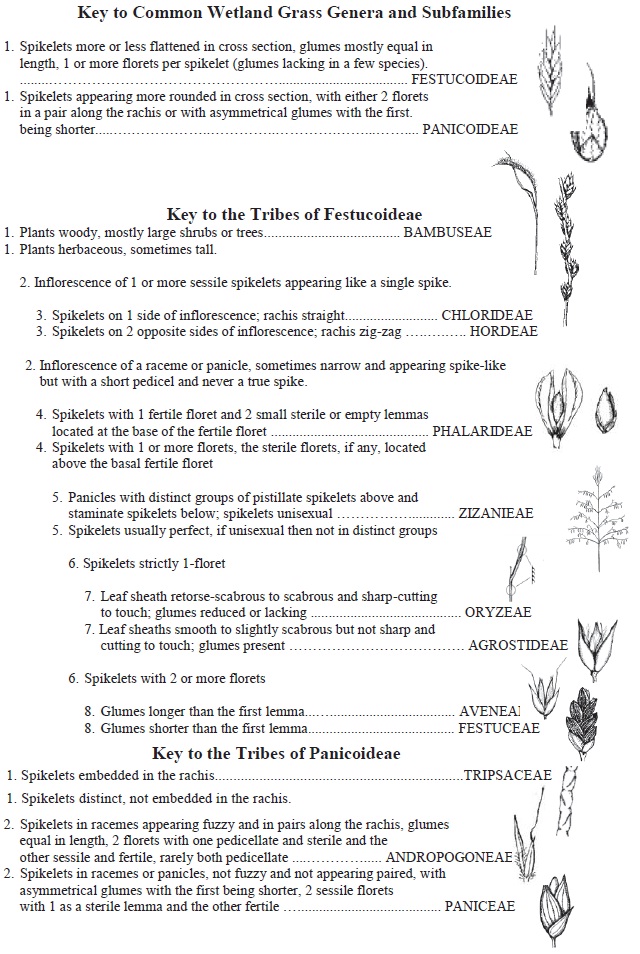

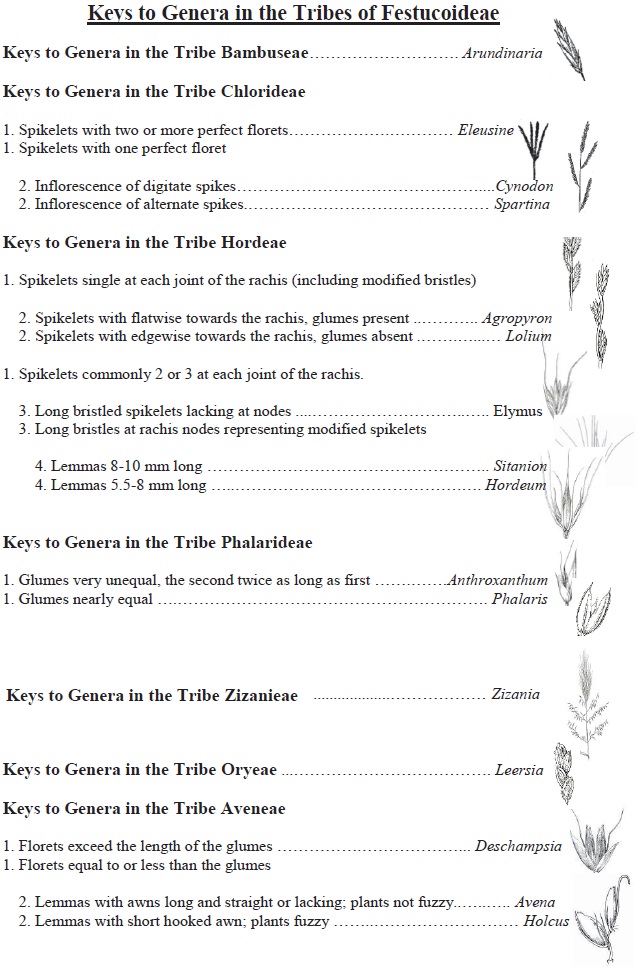

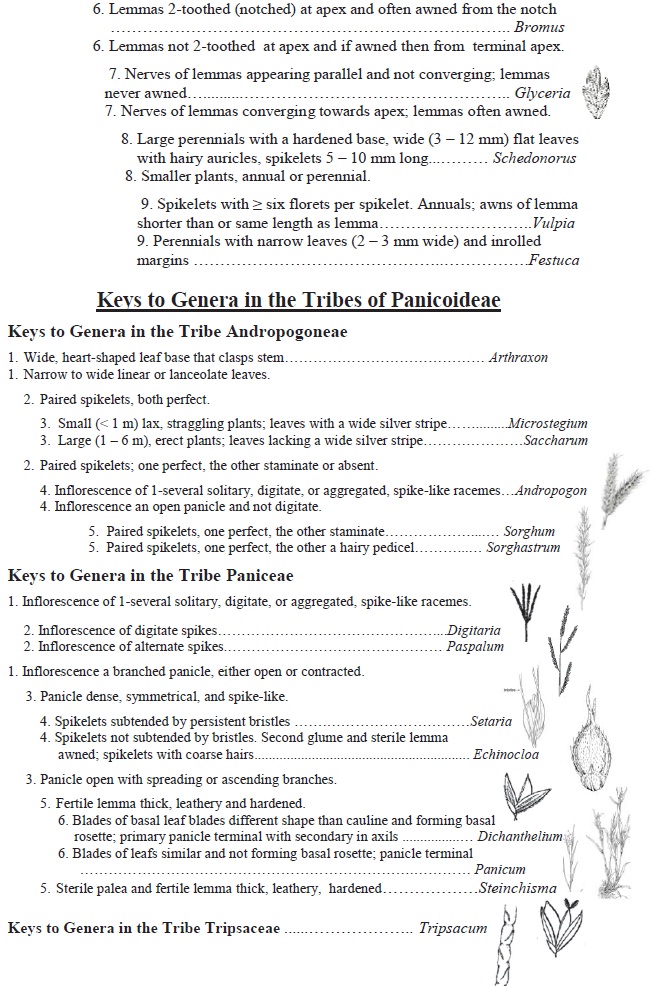

| Tribe Genera Key |

| Southeast Genera Key |

Episode 18 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Leila Shultz ( Professor Emeritus, Utah State University )

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 19 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Antony A. Reznicek, University of Michigan Herbarium

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 20 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 21 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Gerould Wilhelm

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 22 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Special Guest: Dr. Gerould Wilhelm

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 23 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 24 of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Host: Robert Lichvar, Research Botanist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Supported by the National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) and the Wetland Regulatory Assistance Program (WRAP).

Episode 1a: Overview of All Things Wetland Plants Video Series

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 1b: Introduction to Plant Identification

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 2a: Natural History of Ferns : with Paul Wolf

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 2b: Identifying Ferns : with Paul Wolf

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 3: What is Common?

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 4: Wetland Ratings

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 5: Dichotomous Keys

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 6a: A Discussion of Herbaria : with Dr. William Weber

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 6b: A Lifetime of Botany : with Dr. William Weber

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 6c: A Reading on the Concept of a Genus : with Dr. William Weber

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 7: Plant Sampling for DNA : with Paul Wolf

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 8: Keying Common Wetland Ferns

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 9: Natural History of Savannah Lowland Swamps : with David Lekson

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 10: Key Features for Identifying Willows : with Robert Dorn

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 11: Wetland Fungi Demystified : with Dr. Gary Laursen

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 12: A Tour of the U.S. National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 13: Overview of Grasses

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 14: Overview of Blue Spruce Wetland Frequency Study

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 15: Identifying Common Wetland Flowering Plant Families

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 16: Identifying Common Equisetums

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 17: Identifying Common Grasses

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 18: Floristic Regions : with Dr. Leila Shultz

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 19: Carex (Sedge) Identification : with Dr. Anton Reznicek

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 20: Identifying Eastern Woodies : with Jennifer Goulet

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 21: Floristic Quality Index : with Dr. Gerould Wilhelm

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 22: Why Don't We Use Lichens for Wetland Delineation? : with Dr. Gerould Wilhelm

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 23: Identifying Common Sedges

Watch on YoutubeEpisode 24: Identifying Common Rushes

Watch on Youtube